Beethoven: Divine Flame of Immortal Genius

The year 2020 marks the 250th anniversary of the birth of one of the world’s greatest musical geniuses of all time: Ludwig van Beethoven.

This hallmark will be celebrated with events all around the world throughout the year, all under the official anniversary flag of BTHVN2020, sponsored by the German government.

A splendid occasion to remember why Beethoven’s figure is still relevant, debunk some myths about the man, and learn why his influence meant a radical change in music.

Beethoven at age 13.

Known simplistically as a gruff, tormented, deaf musician with wild hair, Beethoven was a bit of a child prodigy with a unique gift for melody and improvisation, which would drive his father mad during practices and rehearsals.

Although trained in the classical tradition of Bach, Scarlatti, Mozart and Haydn (his teacher), these gifts would be the cornerstone for his singular compositions.

As a young musician of 16, Beethoven met Mozart, and asked him to pick a theme for him to improvise. It is said that at the end of the meeting, Mozart commented of him: “watch out for him; someday he’ll give the world something to talk about.”

As a composer, Beethoven constantly pushed the envelope, taking musicians, singers, instruments and audiences to extremes never before seen, becoming instrumental in the redesign of the piano, and setting the standard for a whole new musical style - Romanticism.

Although nowadays we may consider Beethoven’s music as ‘classical’, back in his time he broke all rules and conventions in order to create music capable of incredible lyricism, of emotional depths unknown until then, radically different to anything heard before.

In fact, if anything, Beethoven was a true rebel of the music scene.

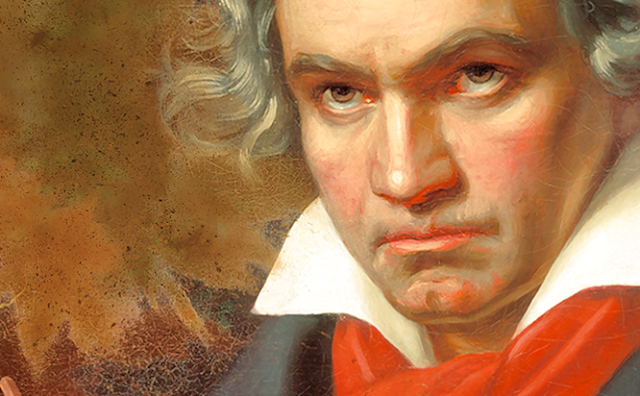

Oil portrait by Christian Hornemann, 1802

One of the main misconceptions is that Beethoven was a deaf musician.

Although by the end of his life, at age 56, he was almost certainly completely deaf, Beethoven did not begin to lose his hearing but until age 28, after a strange illness, which modern doctors have described as a possible meningitis.

This meant that, although he was progressively losing listening sensitivity, Beethoven already had a built-in musical memory, musical imagination, and extensive experience reading and writing music, all of which allowed him to ‘hear’ the sounds of music in his mind before translating them onto paper or to the keyboard.

We can not know for sure how Beethoven might have heard his own music as his deafness progressed, but we know that this illness influenced the character of his music and his need for loudness.

Oil portrait by Willibrord Joseph Mahler, 1805

One of the Beethoven’s innovations was the use of the fortepiano as his main instrument to compose and perform, due to its range and expressive capabilities.

Invented around 1700, the fortepiano had been used by Haydn and Mozart in several well-known compositions before, but its expressive capabilities had not yet been fully explored. Even the technique to play it was different, almost delicate, similar to the technique for the harpsichord.

But Beethoven changed all that, demanding from its fortepiano makers bigger resonation boxes and stronger strings that could withstand his pounding, developing a new playing technique that would extract every bit of expression available from the instrument.

And yet, even with all these changes, he complained that the sound range available on the keyboard was too limited - his music was boundless.

Beethoven’s changes to the fortepiano propelled the evolution of the instrument into the pianoforte, the predecessor of the modern piano that we know today.

Beethoven, Piano Concerto No.5 in E flat major, Op.73 “Emperor”

2nd Movement - Soloist: Claudio Arrau (8:28")

Another innovation came from the music itself.

Paid by wealthy patrons, music was meant to be a mere background for the frivolous conversations of the aristocracy in their social reunions. Anything disturbing it was frowned upon.

However, Beethoven refused to serve as a mere backdrop - he demanded attention!

In the late XVIII century, music followed a predictable structure, following the classical canon. But Beethoven shattered these rules in order to achieve greater expression.

Beyond being merely entertaining, Beethoven sought to move the listener with his music. He sought to stir emotions, incite the imagination, bewilder, surprise, shock, move.

But his passionate, unexpected, sometimes exuberant music was not everyone’s cup of tea.

However, with the onset of the French Revolution, the time was ripe for greater avenues of expression, and Beethoven’s music flourished in the often chaotic ambient of the era.

One of the changes proposed by Beethoven’s music was omitting the typical build up in a crescendo before a big explosion of sound.

Instead of building up, Beethoven often passed abruptly from delicate softness to resounding loudness, in order to enhance the sentiment, sometimes inserting long silences before startling the audience with a loud bang of music.

Another change was the use of dissonant chords in order to depict a particular state of mind, a change of emotion, etc. None of this was well-received by either the audience or the musicians.

In fact, with its abrupt changes and loudness, his music was ‘hard’ on the ears of those who wanted to concentrate on their chit chat. Listeners complained that his music was ‘too loud’ and ‘chaotic’. Even musicians complained that it was ‘too complex’ and ‘unplayable’.

However, some listeners did appreciate the bravado of his music, and Beethoven found wealthy patrons to fund his composing.

Sketches of Beethoven during one of his walks.

One of the greatest innovations delivered by Beethoven was his ability to create ‘musical imagery’.

Although previous composers such as Vivaldi, Mozart, Haydn and Joseph Boulogne were extremely skilled at creating delightful musical passages that stirred the imagination, Beethoven’s music went much further.

While these composers could describe vivid images from the world around us (landscapes, animals, weather, people, events, etc.), Beethoven’s music was capable of projecting vivid depictions of the invisible: thoughts and ideas, moods and emotions - inner life.

This made his music sometimes incomprehensible to listeners used to hear only what they could see. In order to enjoy it, they had to seek within. This meant an extra effort of introspection that many were not prepared to make.

But once the public paid attention, the message in his music became clear and unmistakable, earning him a growing trove of admirers.

Violin Romance No. 2 in F major, Op, 50 (9:50)

Befitting the image of ‘mad genius’, Beethoven was often so absorbed in his creations that he reserved little to no thought to his living conditions, and to trifles such as tidying up, shaving or changing clothes.

Also, he often composed well into the night, singing out brokenly and banging his piano in order to hear the notes, careless about the complaints of his sleepless neighbours.

As it is well-known, Beethoven liked to go out for strolls in the forests around Vienna, carrying a bunch of paper and a pencil to jolt down musical fragments and ideas for harmonies whenever inspiration struck.

This love for nature is evident in many of his compositions, but specially in his 6th Symphony, “Pastorale”.

The piece was meant to depict a German rural festival, but it’s best-known portrayal is as a mythological divertimento in Walt Disney’s “Fantasia” (1940).

This abridged version was much criticised by musical purists, but for many children it was the first introduction to Beethoven and it opened the doors to the enjoyment of classical music.

Often depicted as a gruff old man with wild hair, many forget and ignore that Beethoven had a great sense of humour and a zest for life.

This and his affable character earned him no few friends and popularity within social circuits, which he used skilfully to make connections, win the favour of patrons and land commissions.

Examples of his humour and playfulness abound in his compositions, particularly those for piano or chamber music.

However, as his deafness progressed and the ails of ill health, old age, financial and personal problems plagued him, his character eventually soured.

This was also reflected in his music, sometimes in arrests of anger, but mostly in soulful, meditative passages, such as in the first movement of the Piano Sonata No.14, Opus 27, “Moonlight”, which reveal his despair, suffering and sombre mood.

However, his spirit refuses to succumb, and even in his darkest moments his music always depicts a glimmer of hope.

Some of Beethoven’s most sublime compositions emerged from his most troubled times, revealing his courage and humanity, and the greatness and invincibility of his spirit.

In the manner of true great artists, Beethoven managed to turn his own suffering into everlasting beauty for everyone to enjoy.

Beethoven at 56

Beethoven’s enduring legacy has survived through the centuries, and his music has never fell out of favour with the public or fallen out of fashion.

In 1977, Walter Murphy & the Big Apple Band reached the top on the pop music charts with his disco version of excerpts from the first movement of Beethoven’s fifth symphony.

The version, called “A Fifth of Beethoven”, was also included in the soundtrack of the cult film “Saturday Night Fever”.

Walter Murphy - A Fifth of Beethoven (3:03")

In fact, pop culture has never been too far from Beethoven.

Back in 1956, Chuck Berry composed his Rhythm & Blues hit “Roll Over Beethoven”, which topped the charts, was famously covered by The Beatles, and is still considered one of the best pop songs of all times.

Although the lyrics express the wish for pop music to replace classical music, it helped nonetheless to popularize even more the name of the famed composer.

In addition, Charles Schulz, creator of the cartoon strip “Peanuts” introduced Beethoven (his favourite composer) to generations of children by making him the favourite composer of his pianist character, Schroder.

Schroder Adagio Cantabile (3:39")

More recently, Beethoven has made his way into children’s books, one of which, “Beethoven Lives Upstairs”, a fictional story from the point of view of a young neighbour in Vienna, was also made into a feature film.

Beethoven Lives Upstairs, by Barbara Nichol

Illustrations by Scott Cameron

All of these have helped to keep Beethoven’s fame alive, fuel the interest in his legend, and introduce his music to larger audiences.

However, the best way to understand the Maestro is to simply sit back and listen to his music, allowing it to take us to whatever emotional state it may lead us.

Possibly the main reason for Beethoven’s undying endurance lies in the relatable nature of his music.

We can all relate to the moods and emotions expressed in his music: joy, elation, confusion, despair, hope, anger, wonderment... At one time or another we have all experienced these, and in hearing these feelings echoed in his music we feel understood, in good company.

Manuscript music score by Beethoven of his Piano Sonata in A flat

In 1985, The European Union chose a version based on Beethoven’s Ode to Joy as its official anthem, chosen to represent the shared values of all its members.

But perhaps the greatest evidence of Beethoven’s universality was to be included in the golden records carried by the Voyager probes sent by NASA to outer space in 1977, which contained greetings and selected sounds to represent the human race and our planet.

Maybe another race out there will listen to his Fifth Symphony and feel as moved as we do.

Nearly two centuries after his disappearance, Beethoven’s genius continues to move generation after generation of listeners, his spirit alive in each one of his compositions, which still today keep on arising deep emotions, flaring passions and reminding us that we all are members of the human race, connected to nature and all living creatures - a small but significant dust spec in the vastness of the eternal universe.

To learn more...

To learn more about the worldwide events taking place this year to celebrate Beethoven’s birth, go to the official Beethoven 2020 Anniversary page :

To see some of Beethoven’s personal objects in Heiligenstadt, where he sought a cure for his deafness and wrote his testament, check out the Beethoven Museum in Vienna:

To see Beethoven’s birthplace and pay a virtual visit, visit the Beethoven House Museum in Bonn:

To see one of the apartments where Beethoven lived in Vienna, containing many of his personal objects (including his piano), and where he completed the Fifth and Sixth symphonies, check out the Pasqualati House Museum in Vienna:

Sources: BTHVN2020, Wikipedia, Great Composers: Beethoven Ludwig van.

Comments

Post a Comment